Table of Contents

Why Prototyping Problems Rarely Start With the First Sample

In many product development projects, nothing seems wrong at the beginning. The first prototype arrives on time. The finish looks acceptable. The team moves forward. Problems usually surface later—during the second or third revision.

Suddenly, small changes require long explanations. Previously settled decisions are reopened. Feedback cycles stretch. At that point, teams often realize the issue is not the design itself, but the way prototyping decisions were made early on.

This article is written for teams actively selecting a prototyping partner. Rather than offering generic advice, it focuses on practical decision-making: how to recognize early warning signs, how to evaluate trade-offs, and how to avoid mistakes that only become obvious when changing direction has already become expensive.

Prototyping Is a Decision-Making Phase, Not an Execution Step

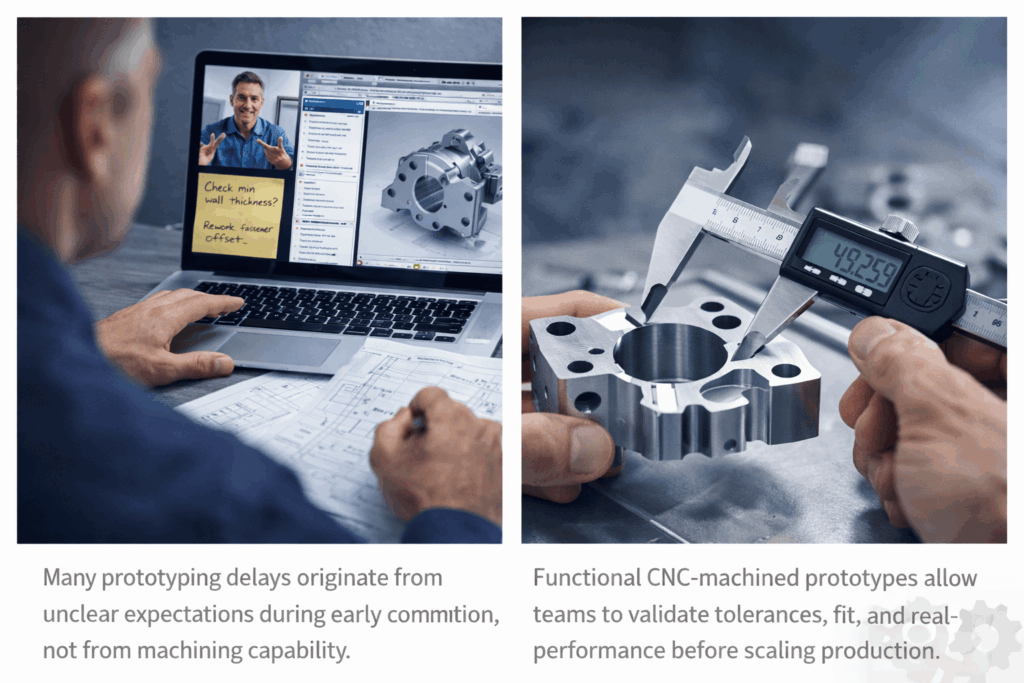

Many teams treat prototyping as a straightforward execution task.

Once the design is “ready enough,” files are sent out, and the next milestone is scheduled.

This assumption causes problems because prototyping is rarely about producing a final answer. It is about testing assumptions—often incomplete or unproven ones.

At this stage, designs change for reasons that are not always visible in drawings. A tolerance turns out to be too tight. An assembly step becomes awkward. A material behaves differently under real use. When this happens, the role of the manufacturer shifts from execution to interpretation.

If a partner treats drawings as fixed instructions, every change becomes a reset. Context must be re-explained. Feedback loses continuity. Iteration slows—not because machining is difficult, but because decision-making loses momentum.

This is why prototyping should be treated as a decision-making phase. The value lies not only in the parts produced, but in how quickly uncertainty is reduced.

The Most Common Prototyping Mistakes — And How to Recognize Them Early

Most prototyping failures are not caused by poor technical capability. They are caused by early judgments that feel reasonable at the time. Below are the most common ones.

Choosing Based on Price Before Understanding Interaction Cost

Comparing quotes is normal. Ignoring interaction cost is not. In prototyping, the most expensive delays rarely come from machining itself. They come from repeated clarification—explaining design intent again, correcting assumptions, and re-aligning expectations after each revision. When every design change requires a full reset, progress slows quickly.

A familiar scenario for many teams looks like this: by the third revision, the same CAD file has been explained multiple times—yet it still produces a different interpretation each round.

One of the earliest warning signs appears during the RFQ stage. Does the supplier ask clarifying questions about validation goals, iteration expectations, and critical features—or do they simply confirm feasibility and price?

Experienced teams evaluate a prototyping manufacturer not by unit cost alone, but by how effectively they support iteration, technical discussion, and early-stage feedback.

Asking “Can This Be Made?” Instead of “Should This Be Made Now?”

Early in development, feasibility is rarely the real constraint. Timing is. Some solutions are technically possible but introduce unnecessary rigidity. Others work well for validation but would be unsuitable later. If this distinction is never discussed, teams may lock themselves into decisions that feel efficient early but become expensive to reverse.

A practical rule of thumb is this: if a manufacturing choice reduces your ability to change direction later, it deserves extra scrutiny—especially during prototyping.

Assuming Clear Drawings Eliminate the Need for Judgment

Even with detailed drawings, prototyping involves interpretation. Tolerances, material substitutions, and manufacturability decisions often require experience-based judgment.

When suppliers avoid these conversations, teams are left to discover issues through trial and error. That learning process is rarely cheap.

Treating the Prototype as an Endpoint

A prototype is not a conclusion; it is a checkpoint. If the manufacturing method used during prototyping has no relationship to later production, much of the validation effort becomes isolated knowledge. What looks like cost efficiency early often returns later as redesign, requalification, or process changes.

What Actually Makes a Prototyping Partner Reliable

Reliability in prototyping has little to do with owning the largest equipment list. It is defined by how decisions are handled when information is incomplete. In practice, three indicators matter most.

First: clarity on validation intent.

Reliable partners ask what the prototype is meant to prove—fit, function, durability, or manufacturability—and adjust decisions accordingly. This prevents over-engineering early samples or locking in unnecessary constraints.

Second: early risk exposure.

They surface risks before production begins: aggressive tolerances, material limitations, or features likely to cause inconsistency. These conversations may slow momentum briefly, but they prevent far more disruptive problems later.

Third: clear boundaries instead of vague assurances.

Rather than promising everything will work, they explain what tolerances are realistic, what affects lead time, and where costs will increase if requirements change. This transparency reduces false confidence and supports better decision-making.

For teams evaluating how these principles translate into real execution—particularly in CNC-based prototyping and low-volume workflows—you can Lear more Xinprototype to see how CNC machining is applied to early-stage development decisions.

Why CNC Machining Is Often Chosen — And When It Is Not

CNC machining is frequently recommended for functional prototypes, but not because it is universally superior. Its strength lies in predictability. When prototypes must validate material behavior, assembly relationships, or tight dimensional control, repeatability becomes essential. For example, when assemblies depend on tolerances around ±0.05 mm, inconsistent results can invalidate test conclusions.

CNC performs well in these conditions because it reflects real production constraints. The data it produces is easier to trust. That said, CNC is not always the right choice. For early concept validation, visual models, or rapid form exploration, it can be unnecessarily slow or costly. Treating CNC as a default solution can be just as limiting as avoiding it entirely. The key is alignment: matching the manufacturing method to what the prototype is meant to validate at that moment.

Reducing Rework by Moving Risk Forward

Rework becomes expensive when it occurs late—when schedules are tight and options are limited. One advantage of using production-relevant methods like CNC early is that risks appear sooner. Material behavior, tolerance sensitivity, and assembly challenges surface while changes are still manageable.

This does not eliminate risk. It relocates it—making uncertainty visible early enough to act on it. In practice, this often saves more time and cost than it consumes.

Final Thoughts: Making Better Decisions Under Uncertainty

Product development is rarely linear. Designs evolve, constraints shift, and priorities change. The real value of prototyping lies not in producing perfect parts, but in enabling better decisions while change is still possible. Choosing a prototyping partner is ultimately about choosing how uncertainty will be managed.

Good prototyping does not eliminate uncertainty. It makes uncertainty visible early enough to act on it.